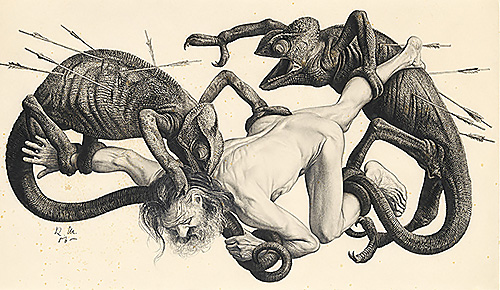

Richard Müller dedicated various drawings and etchings to the subject of the Archer over the course of several decades. A peaceful early version of this theme features a naked, bow-and-arrow-toting hunter who observes flying cranes in a real-to-life landscapes (1897, pencil, 274 x 230 mm, Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig, inv. no. I. 2084), and stands fully in the tradition of his great Saxon predecessor, Max Klinger (1857-1920). According to Müller himself, later variations on this theme were based, however, on the animations of chimeric representations of demons, like those that exist as both a warning and deterrent on Gothic churches. In our large-scale drawing from 1906, Müller has enhanced the nightmarish inversion of the situation through the surreal similarity in size between the hunter and the two chameleons that attack him. The archaic-looking nude has already lost his weapon here; only the arrows in the animals‘ backs and the title of the sheet attest to the fact that he, too, has made any attacks before this point. The balance of power has obviously shifted, however; the hunter is at the mercy of his supposed victims, who take cruel revenge in delivering this fight to the death. The terrified viewer is left only to speculate whether the unfortunate man will die from being torn apart or from being bitten in the neck.

Richard Müller created two additional variants on this theme: in the first, the hunter – with broken weapons, and the hare he has recently shot still in his hand – fights a hopeless battle against an enormous boa constrictor. The second variant features a single, larger-than-life chameleon with two bowmen who are, once again, overcome by their presumed victim (Fig. 1). A few years later, Richard Müller translated all of these versions into corresponding etchings.